DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU

More on DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU

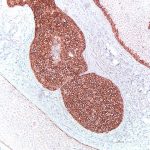

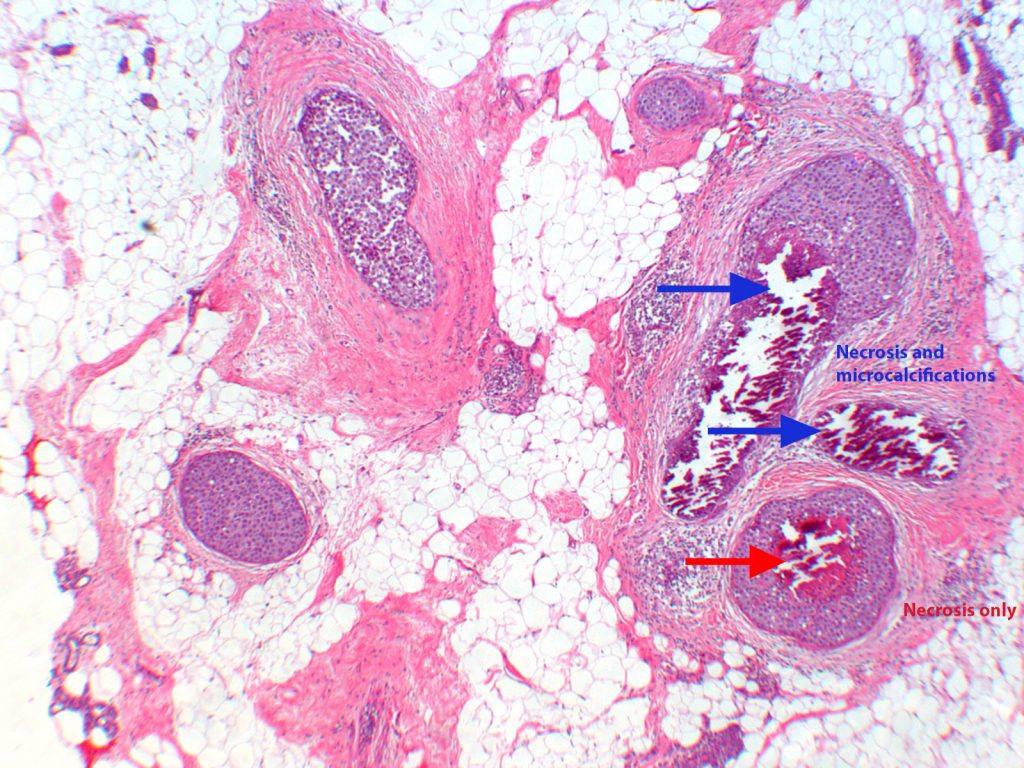

The definition of ductal cell carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a progressive growth of malignant cells contained within the ductal system of the breast. This unrestricted “intra-ductal” growth of the malignant cells tends to expand the size of the ducts, sometime greatly as seen above. If the malignant cells grow too fast, cells toward the middle of the duct die in a process called necrosis. Calcium deposits often form when there has been necrosis of cells and it happens within DCIS as seen above. But not every duct involved with DCIS has necrosis and even those with necrosis, may not have calcifications present.

What can be seen above is a cross-section of six ducts. Three ducts have necrosis and three do not have necrosis. Two of the three ducts with necrosis also have large deposits of calcium, also called microcalcifications. (See blue text and arrows). There is one duct with necrosis only. (See red text and arrow)

Another point about DCIS is that malignant cells are growing all the time. In the case of DCIS, the malignant cells to grow within the duct system, like water flows through a pipe system. In the breast, all ducts lead toward the nipple. This means that malignant cells can extend down the ductal system and the extent can be best detected if calcium deposits are being formed. Otherwise its growth is hidden or stealth-like.

When a lumpectomy is performed, the margins of the resection are thoroughly examined by the pathologist. If DCIS is present or very close to any margin, this causes the surgeon and radiation oncologist to be concerned about the recurrence of the disease. Either of these physicians will talk to you more about this issue if it is appropriate to do after the final pathology report has been issued.

In planning the lumpectomy procedure, the surgeon and mammographer review all breast imaging material to determine how to best remove the breast abnormality with adequate margins. Localization wires may be placed prior to surgery to delineate the extent of disease that can be detected on mammogram or other imaging techniques.

Immediately after the diseased tissue excision (lumpectomy), a two-way “mammogram” is taken (at 90 degree angles) in an attempt to assess margins of the excision while the patient is still in the operating room. Suffice it to say, every effort is made to “get clean margins” on the first attempt.

When the specimen reaches the pathology lab it is fixed overnight so that it will be prepared for sectioning and microscopic analysis. A pathologist examines every section of the lumpectomy; most lumpectomies are routinely submitted totally. This practice ensures that all margins are examined under the microscope and the findings are summarized in the final report.

This examination of margins under the microscope may find previously undetected DCIS at or near the margin. How does this happen? (See photograph) This kind of DCIS does not form a mass or something that you can palpate or feel. Three of the ducts in this picture have no necrosis or calcifications. Without calcifications, the mammographer cannot see the extent of the DCIS as it extends to or near the margin. In this case photographed on the first page, close margins would have been detected by the specimen “mammogram” and if necessary additional margins would be taken during the first surgery.

UNWANTED SURPRISE:

It is the pathologist who finds the undetected DCIS at the margin because of a thorough examination of the lumpectomy specimen. If there is a problem margin, typically there are a few ducts that have reached the margin edge undetected until the pathologist finds the problem. Usually this problem margin is away from the known disease that is centered in the lumpectomy. It is this careful assessment by the pathologist that allows the patient’s doctors to plan her treatment based on accurate information.